Key points

- Shading your home, particularly windows and other forms of glazing, can have a significant impact on summer comfort and energy costs.

- Appropriate shading designs and structures can help to block unwanted sun in summer while still allowing solar access in winter.

- Shading can be fixed (for example, eaves, fences and evergreen trees) or adjustable (for example, external louvres, pergolas with adjustable shade cloth, blinds and deciduous trees).

- Shading should work with orientation to make your home comfortable and reduce your energy costs. For most of Australia, north is the ideal orientation for glazing, and also the simplest to shade. However, appropriate shading solutions are available for any orientation.

- On north-facing façades, the easiest shading solution is eaves that are wide enough to block high-angle sun in summer but admit low-angle sun in winter. Horizontal shade projections above glazing can also work well.

- On east-and west-facing façades, vertical shade structures or deep pergolas work well, particularly if they are adjustable, allowing you to let in winter sun when needed.

- More shading is suitable for warmer tropical climates, and less shading may be suitable for cold climates.

- Plants can provide good shading and can also improve cooling, air quality and visual appeal of your home.

Understanding shading

What is shading?

Shading simply means blocking the direct rays of the sun. For your home, shading can be provided by fixed or adjustable building elements such as eaves, awnings, fences, external blinds and trellises, or by natural elements such as trees and shrubs. Your home may also be shaded by nearby buildings and other features.

The best approach to shading your home depends on your climate and your building’s orientation. For warmer climates you may want to optimise shading, for mixed climates you may want to let sun into your home in winter and shade it in summer, and for cold climates you may want to minimise shading.

Sun angles

In designing appropriate shading for your home, it is helpful to know the angle at which the sun will hit your home, and especially any north-facing windows, in different seasons.

There are apps available to assess sun angles for your region, and many designers have drafting software that calculate sun angles and shadows for various locations and topographies based on a digital site survey.

You can also calculate the angle of the sun in the sky at noon for the solstices and equinoxes, based on your latitude. The calculation is:

For insulation to be effective, it should work in conjunction with good passive design. For example, if insulation is installed but the house is not properly shaded in summer, built-up heat can be kept inside by the insulation, creating an ‘oven’ effect.

- Equinox = 90° — latitude

- Summer solstice = Equinox + 23.5°

- Winter solstice = Equinox — 23.5°.

Source: Energy Smart Housing Manual (2018 )

The latitudes of main Australian cities are included in the following table. Geoscience Australia allows you to find the latitude of more than 250,000 places in Australia and calculate the sun angle at any time of the day, on any day of the year.

Latitude of main Australian cities

| City | Latitude |

|---|---|

| Darwin | 12.42°S |

| Cairns | 16.92°S |

| Broome | 17.96°S |

| Townsville | 19.25°S |

| Rockhampton | 23.37°S |

| Brisbane | 27.38°S |

| Geraldton | 28.77°S |

| Perth | 32°S |

| Sydney | 33.86°S |

| Adelaide | 35°S |

| Canberra | 35.28°S |

| Melbourne | 37.97°S |

| Hobart | 42.88°S |

Why is shading important?

Direct sun can generate the same heat as a single bar radiator over each square metre of a surface, but effective shading can block up to 90% of this heat. By shading a building and its outdoor spaces, we can reduce summer temperatures, improve comfort and save energy.

Photo: Architect Brian Meyerson

Radiant heat from the sun passes through glass and is absorbed by building elements and furnishings which then re-radiate it inside the dwelling. Re-radiated heat has a longer wavelength and cannot pass back out through the glass as easily.

In most climates, solar gain is desirable for winter heating but must be avoided in summer. Shading glass is the best way to reduce unwanted heat gain, as unprotected glass is often the greatest source of heat entering a home. Shading uninsulated and dark-coloured walls can also reduce the heat load on a building. However, fixed shading that is inappropriately designed can block beneficial winter sun.

Achieving good shading

General guidelines for all climates

Some general principles can be followed for most regions and climates in Australia. However, shading requirements will vary according to your home’s orientation.

Orientation and suggested shading types

| Orientation of living areas | Suggested shading type |

|---|---|

| North | Fixed or adjustable horizontal shading above window and extending past it each side |

| East and west | Fixed or adjustable vertical louvres or blades; deep verandas or pergolas with deciduous vines |

| North-east and north-west | Adjustable shading or pergolas with deciduous vines to allow winter solar heating or verandas to exclude it |

| South-east and south-west | Planting: deciduous in cool climates, evergreen in hot climates |

For north-facing living areas, sun can be excluded in summer and admitted in winter using simple horizontal devices, including eaves and awnings. North-facing openings (and south-facing ones for areas above the Tropic of Capricorn) receive higher angle sun in summer and therefore require narrower overhead shading devices than east- or west-facing openings.

East- and west-facing openings require a different approach, as low-angle morning and afternoon summer sun from these directions is more difficult to shade. Keep the area of glazing on the east and west orientations to a minimum, or use appropriate shading devices. Adjustable vertical shading, such as external blinds, is the optimum solution for these elevations.

Deep verandas, balconies or pergolas can be used to shade the eastern and western sides of the home, but may still admit very low-angle summer sun. Use in combination with planting to filter unwanted sun.

Photo: QMBA/Your New Home Magazine

Plants can be used for shade, especially for windows. Evergreen plants are recommended for hot humid and some hot dry climates. For all other climates, use deciduous vines or trees to the north, and deciduous or evergreen trees to the east and west.

Photo: Sunpower Design

Protect skylights and roof glazing with external blinds or louvres. This is crucial because roof glazing receives almost twice as much heat as an unprotected west-facing window of the same area. Quite small skylights can deliver a lot of light, so be conservative when sizing them.

Position openable clerestory windows to face north, with overhanging eaves to exclude summer sun. Double glaze clerestory windows and skylights in cooler climates to prevent excessive heat loss.

Climate-specific designs

Shading approaches can be tailored to suit your climate zone. Find out more about building for your climate zone on the Design for climate page.

Hot humid climates (Climate zone 1 and some parts of zone 2)

- In hot humid climates, shade the walls year round and consider shading the whole roof. A ‘fly roof’ can be used to shade the entire building. It protects the core building from radiant heat and allows cooling breezes to flow beneath it.

- Shade all external openings and walls including those facing south.

- Use covered outdoor living areas such as verandas and deep balconies to shade and cool incoming air.

- Use shaded skylights to compensate for any resultant loss of natural daylight.

- Choose and position landscaping to provide adequate shade without blocking access to cooling breezes.

- Use plantings instead of paving to reduce ground temperature and the amount of reflected heat.

Hot dry climates (Climate zones 3 and 4)

- Shade all external openings in regions where no winter heating is required.

- Provide passive solar shading to north-facing openings in regions where winter heating is required.

- Avoid shading any portion of the glass in winter when winter heating is required — use upward raked eaves to allow full winter solar access, or increase the distance between the window head and the underside of the eaves.

- Use adjustable shade screens or deep overhangs (or a combination of both) to the east and west. Deep covered balconies or verandas shade and cool incoming air and provide pleasant outdoor living spaces.

- Place a shaded courtyard next to the main living areas to act as a cool air well. Tall, narrow, generously planted courtyards are most effective when positioned so that they are shaded by the house.

- Use plantings instead of paving to reduce ground temperature and the amount of reflected heat.

Warm humid and warm/mild temperate climates (Climate zones 2, 5 and 6)

- Provide passive solar shading to all north-facing openings, using shade structures or correctly sized eaves.

- Use adjustable shade screens or deep overhangs to the east and west. Adjustable shade screens that exclude low-angle sun are most effective.

Cool temperate climates (Climate zone 7)

- Avoid shading any portion of the north-facing glass in winter — use upward raked eaves to allow full winter solar access, or increase the distance between the window head and the underside of the eaves.

- Use deciduous planting to the east and west. Avoid plantings to the north that would obstruct solar access.

- Do not place deep covered balconies to the north as they obstruct winter sun. Balconies to the east or west can also obstruct winter sun to a lesser extent.

Photo: Warren Reed (© Beaumont Building Design)

Fixed shading

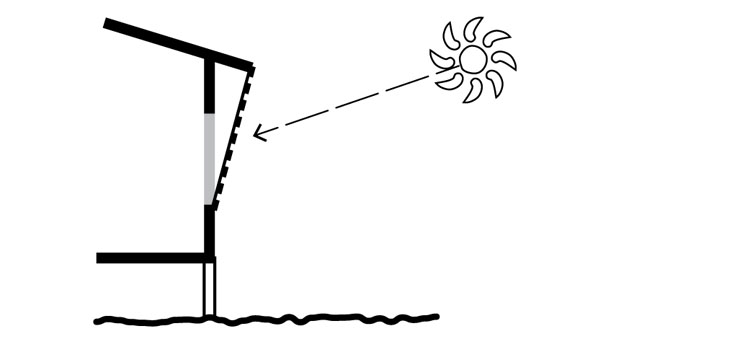

Summer sun from the north is at a high angle and is easily excluded by fixed horizontal devices over openings. Winter sun from the north is at a lower angle and penetrates beneath these devices if correctly designed.

Fixed shading devices (eaves, awnings, pergolas and louvres) can therefore regulate solar access on northern elevations throughout the year, without requiring any user effort.

Eaves

Correctly designed eaves are generally the simplest and least expensive shading method for northern elevations and are all that is required on most single-storey houses.

Width

As a rule of thumb, your eave width should be 45% of the height from the bottom windowsill to the bottom of the eaves. This ensures that north-facing glass is fully shaded for a month either side of the summer solstice and receives full solar access for a month either side of the winter solstice.

Aim for consistent sill heights where possible and consider extending the eaves overhang over full height doors or windows. This allows the 45% rule to be simply met with the following standard eaves overhangs of:

- 450mm when the height from sill to eaves is 900–1200mm

- 600mm when the height from sill to eaves is >1200–1350mm

- 900mm when the height from sill to eaves is >1350–2100mm

- 1200mm when the height from sill to eaves is 2100–2700mm.

Where sill heights vary on a single north façade, set your eave overhang to the average sill-to-eave height of larger glass areas. In warmer climates, go up to the nearest size in overhang; in cooler climates, go down to the nearest size.

Varying the rule of thumb

You can fine-tune your passive shading by varying the 45% rule of thumb for eave width to suit your regional climate, topography and house design. Find out more about your climate zone on the Design for climate page.

For example, reduce the overhang by decreasing the percentage of the sill-to-eave height by up to 3% to extend the heating season:

- at higher altitudes (for example, eastern highlands, tablelands and alpine regions)

- where cold winds or ocean currents are prevalent (for example, southern Western Australia and South Australia)

- in inland areas with hot dry summers and cold winters (for example, Alice Springs)

- in cold, high-latitude areas (for example, Tasmania and southern Victoria).

Gradually increase the percentage of height (and corresponding width of eaves) as heating requirements decrease in latitudes north of 27.5°S (Brisbane). This will decrease or eliminate the amount of sun reaching glass areas either side of the equinox:

- for hot dry climates with some heating requirements, gradually increase the overhang up to 50% of height (full shading)

- for hot humid climates and hot dry climates with no heating requirements, shade the whole building at all times with eave overhangs of 50% of height from floor level to both north and south façades where possible, and use planting or adjoining buildings where it is not possible. East and west elevations require different solutions.

Photo: Simon Wood Photography

Position

To avoid having permanently shaded glass at the top of the window, ensure that distances between the top of glazing and the eaves underside are at least 30% of the height. This is actually a more important component of eave design than width of overhang, especially in cool and cold climates where it is a significant source of heat loss at night with no compensating daytime solar gains. It is not always achievable with standard eaves detailing that are flush with the 2100mm head (that is height of the top of the window).

Horizontal shading devices must also extend beyond the width of the north-facing opening by the same distance as their outward projection to shade the glass before and after noon.

Source: Sustainable Energy Authority Victoria

Design

North-facing upward raked eaves allow full exposure of glass to winter sun and shade larger areas in summer, without compromising the solar access of neighbours to the south. A separate horizontal projection of metal louvres shades lower glazing. This allows 100% winter solar access and excludes all sun between the spring and autumn equinoxes.

Architects: Environa Studio; Photo: SIMART

Louvres

Fixed horizontal (overhead) louvres set to the noon mid-winter sun angle and spaced correctly allow winter heating and summer shading in locations with cooler winters. As a rule of thumb, the spacing between fixed horizontal louvres should be 75% of their width. The louvres should be as thin as possible to avoid blocking out the winter sun.

Fixed shading for east and west

West-facing glass and walls are a significant source of heat gain in hotter climates. East-facing glass can be equally problematic because, while the home is cooler in the morning and heat gains do not cause noticeable discomfort, it is the start of a cumulative process that causes thermal discomfort in the afternoon and early evening. Both east and west require shading in hotter climates. In cooler climates, east shading is a lower priority.

Because east and west sun angles are low, vertical shading structures are useful to allow light, views and ventilation while excluding sun. Roof overhangs, pergolas and verandas that incorporate vertical structures such as screens, climber-covered lattice and vertical awnings are also effective.

Source: Townsville City Council

Source: Townsville City Council

Adjustable shading

Adjustable shading allows the user to choose the desired level of shade. This is particularly useful in spring and autumn when heating and cooling needs are variable. However, it is important to note that active systems require active users.

Northern elevations

Adjustable shading appropriate for northern elevations includes adjustable awnings or horizontal louvre systems and removable shade cloth over pergolas or shade sails. Shade cloth is a particularly flexible and low-cost solution.

Eastern and western elevations

Adjustable shading is especially useful for eastern and western elevations, as the low angle of the sun makes it difficult to get adequate protection from fixed shading. Adjustable shading gives greater control while enabling daylight levels and views to be manipulated. Appropriate adjustable systems include sliding screens, louvre screens, shutters, retractable awnings, and adjustable external blinds.

North-east and north-west elevations

Adjustable shading is recommended for north-east and north-west elevations because they receive a combination of high-and low-angle sun throughout the day. Select systems that allow the user to exclude all sun in summer, gain full sun in winter, and manipulate sun levels at other times.

Climate change

Climate change does not affect sun angles, but the desirability of shade or solar heat gain may change, thus affecting the overall design strategy for your home. Adjustable shading (mechanical or seasonal vegetation) means that you can more easily adapt your home to changing climatic conditions.

Photo: Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources

Plants for shading

Plants are low-cost, low-energy shade providers. Plants can also help to block wind, assist cooling by transpiration, improve air quality by filtering pollutants, enhance the visual environment and create pleasant filtered light.

Match plant characteristics (such as foliage density, canopy height and spread) to shading requirements:

- Deciduous plants allow winter sun through their bare branches and exclude summer sun with their leaves.

- Trees with high canopies are useful for shading roofs and large portions of the building structure.

- Shrubs are appropriate for more localised shading of windows.

- Wall vines and ground cover insulate against summer heat and reduce reflected radiation.

Choose local native species with low water requirements wherever possible. Avoid plants with destructive root structures when planting close to the house. Find out more about landscaping and garden design.

References and additional reading

- Cairns Regional Council, Cairns style design guide [PDF],

- Department of Housing and Regional Development (1995). AMCORD: a national resource document for residential development, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

- Hollo N (2011). Warm house cool house: inspirational designs for low-energy housing, 2nd edn, Choice Books, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney.

- Wrigley D (2012). Making your home sustainable: a guide to retrofitting, rev. edn, Scribe Publications, Brunswick, Victoria.

Learn more

- Read Orientation to find out how orientation and shading can work together

- Explore Renovations and additions to find ways to improve your home

- Review Passive cooling for other ways to reduce your need for cooling

Authors

Original author: Caitlin McGee

Updated: Chris Reardon 2013